Over the past few years, leaders and policy makers seeking to change their citizens’ behaviors have grown increasingly aware of the importance of investing in evidence-based policies. Thanks to behavioral economics, they have also come to realise the great utility of crafting a societal environment where better choices and behaviours are simply easier to make.

The pursuit of effective social interventions now routinely features reviews and discussions of scientific support in favor of diverse solutions from financial incentives and regulations to local education programs. And as behavioral economists, we could not be more thrilled to see this growing reliance on science in the pursuit of public good.

At the same time, we feel compelled to turn the tables and raise a different question:

While leaders engineer environments aimed at helping their citizens make better decisions, are their own environments suited to optimal decision-making on the world stage?

A new research study published by a team of Munich University economists weighs in on this dilemma. The scientists provide evidence that leaders’ most common negotiation policies are far from optimal, behaviorally speaking. And it has enormous implications for their ability to solve the ultimate high-stakes dilemma: climate change and environmental degradation.

By digging into a variety of policies that can be deployed to negotiate a climate change agreement, the scientists reveal a strategy that can literally double leaders’ levels of commitment to the cause.

* * *

To consider the challenges leaders face so far, it is worth briefly examining the negotiations which led to the Kyoto Protocol – a 1997 treaty binding 37 industrialised nations to a set of reduced greenhouse gas emission targets. The original aim of the talks was to unanimously agree on emissions caps that were tailored to each participating nation based on their economic status and ability to contribute to combating climate change.

Alas, a lack of unanimous agreement meant that the process devolved into one where each nation nominated their own emissions cap and chose whether they would treat that commitment as binding before the leaders parted ways. Since then, several participating countries have been criticised for failing to meet their self-specified targets. The treaty has not been ratified by the US, while Canada has entirely withdrawn.

Similar shortcomings come into play when we consider the Paris Agreement of 2016. Here, negotiations revolved around agreeing on a complex set of so-called ‘nationally determined contributions’ (in other words: a recapitulation the final stages of the Kyoto Protocol).

While the agreement was a triumph in converting all 196 participating states into signatories, it too has been critiqued for falling short of achieving what is actually necessary to prevent global temperatures from crossing the crucial 2Co delta. Quite simply, most of the agreed-upon emissions targets are simply too small to make that difference, even if met completely – something the UN flagged up in its initial analysis of the treaty.

What we are witnessing, on repeat, is world leaders struggling to translate their good intentions into effective outcomes.

For years, some economists have advocated for a transition to a model centered on achieving mutual agreement on identical commitments from each participating nation, rather than encouraging each party to ‘give what they can’. This suggestion is driven, in part, by the game theory prediction that such a decision-making framework will generate a higher overall investment by virtue of tapping into our primate urges for reciprocity (‘I will if you will’). The more parties agree to partake, the greater that mutual pressure to chip in.

Of course, the method has its share of sceptics. Many remain unconvinced that anything like a uniform commitment can be achieved by a global community rife with ‘messy’ asymmetries in wealth, capabilities, and power. And this is exactly what the researchers behind the new PNAS paper recreated in the behavioral science lab as they set about dissecting and evaluating various negotiation policies.

In their experiment, 500 participants were repeatedly randomized into groups of four to play a public goods game. In this game, each participant is invited to invest an amount of money into a public pool, where it will be multiplied by the researchers prior to being redistributed amongst all parties. While there was no explicit mention of climate change, the game aimed to model a negotiation scenario where individual parties decide how much they wish to pay into a mitigation strategy (e.g., setting an emissions cap or investing in renewable energy) that will ultimately pay off for everyone involved.

Importantly for capturing a ‘messy’ real-life scenario, the researchers gave individual participants differing amounts of starting capital as well as varying degrees of payoff from the public pool. They then set them loose on the task of coming to a mutual agreement.

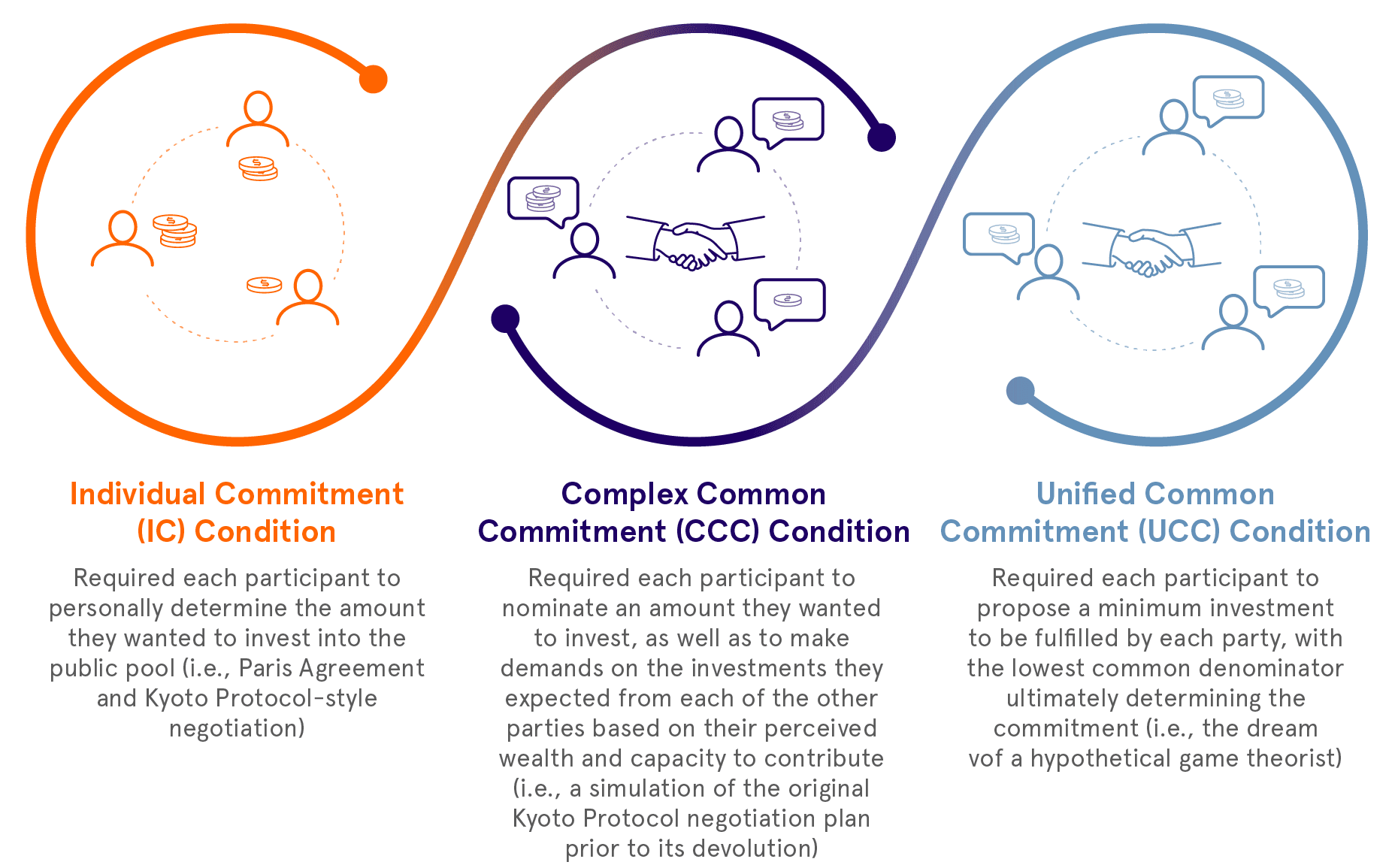

The way groups were instructed to go about their decision-making process differed between experimental conditions, which were defined as follows:

Once the groups formalised their agreements, the researchers dissected how they were influenced by distinct negotiation policies.

What they uncovered is somewhat concerning for those of us who track the outcomes of global climate change summits with much anticipation.

The first crucial observation to emerge was that the condition focused on recreating Paris and Kyoto-style procedures succeeded in attracting a relatively high percentage of individuals to the negotiating table. But it yielded by far the lowest ultimate levels of mutual agreement and investment into the public good. This condition was marginally bettered by the complex common commitment condition (i.e., the initial aspiration for the Kyoto Protocol negotiations). But ultimately, it was the policy requiring participants to focus on reaching a uniform common commitment that came out on top, resulting in roughly 200% higher average investment compared to its competitors.

As the left plot reveals, 83% of participants in the Individual Commitment (IC) condition (i.e. Tokyo- and Paris-style negotiation) agreed to enter negotiations. But negotiations ultimately led less than 50% of groups to reach a mutual agreement. This gap was replicated in the Common Complex Commitment (CCC) condition, and virtually non-existent in the condition requiring Uniform Common Commitment (UCC). The right plot reveals the UCC condition to clearly outperform its competition in terms of the resulting investment in the public good (measured as a % of the socially optimal outcome).

The great outcome gap observed in this research gives us a valuable lesson both in scientific thinking and imagination. Not only does reveal a disconnect between the appeal and performance of our current go-to negotiation policies, but it also raises tantalising questions about what the global community could achieve if only we spent more time vetting our leaders’ decision-making frameworks using scientific methods.

Of course, it is worth remembering that any experiment represents a high-level abstraction from the real-life scenarios that make our choices and behaviours so complex - and this experiment is no exception. Nonetheless, its research insights offer a crucial proof-of-concept that there are steps we can take to nudge ourselves towards more effective action against global warming and environmental degradation.

In the run-up to the next international climate change treaty, we know one question that will be lingering on our minds: will leaders take a cue from scientific evidence and implement a negotiation framework designed to nudge them towards higher levels of commitment?

REFERENCE