For many diseases, medical treatment alone is not enough. A key factor for preventing or slowing the progression of a disease must involve lifestyle changes. Truly improving patient outcomes can only be done by pairing treatments with such health and wellness changes. In this piece, Dr. Matthias Berkes talks about the research behind how we can start helping people incorporate lifestyle and wellness changes into their health plan, and he uses Alzheimer's Disease as an example to illustrate the solutions we can employ.

I want to do a quick exercise. I want you to think of at least two, maybe three, individuals in your life that are above the age of 65. Have them in mind? Their personalities, hobbies, maybe specialty baked goods? You are probably thinking of loved ones, and depending on your age, they may be grandparents, parents, or possibly siblings. Maybe a mentor or a spouse. Alongside their most salient traits — their laughs, their quirks, that twinkle in their eyes — they probably also have concerns related to their health. And unfortunately, odds are fairly high that at least one of the individuals you’ve thought of has received, or is likely to receive, a diagnosis of dementia. Even just reading that term may have instinctively made you shift focus to another individual in your life affected by it.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for ~60-80% of all dementia cases (other causes involve vascular issues or as a result of traumatic brain injury, for example). As such, when we hear someone talk about dementia, there’s a good chance they’re speaking about AD. Symptoms of dementia include issues with memory loss, planning difficulties, language impairment, and often also include behavioral changes and difficulty in performing everyday tasks.

So the symptoms don’t sound great — and they’re not. But should we be concerned? Alzheimer’s is ultimately a disease of aging where an individual’s risk of developing AD doubles every 5 years after the age of 65. Here in Canada, in 2021 there were ~7 million individuals over the age of 65 with a prevalence of dementia of ~7% (or about 450k affected individuals). Worldwide, approximately 55 million individuals are affected, with that number expected to rise to 78 million by 2030. Societally, the global cost of dementia was approximated at ~$1.9 trillion(!) in 2019. Pharmaceutical treatments vary in their effectiveness in treating the symptoms of AD with no guaranteed cure at present. Every diagnosis of dementia includes enormous emotional, social, and physical costs for the affected individual and their loved ones.

This sounds like a lot of doom and gloom, but there is one potential ray of light. In the current absence of a pharmaceutical cure for AD, the key to handling dementia may lie in preventing or delaying symptoms. We can’t do anything about risk factors like age and genetics, but individuals can take control over lifestyle factors that have been shown to prevent or delay dementia symptoms and onset. What do we mean when we discuss ‘lifestyle factors’? Simply put, these are any lifestyle choices and activities that have positive benefits for healthy cognitive aging. Factors like engaging in effortful physical activity, maintaining a balanced and healthy diet, and even speaking two languages (i.e., bilingualism) have all been shown to delay the onset of symptoms and improve cognitive outcomes in dementia.

For example, one meta-analysis found that physical activity was associated with an 18% reduction in the risk of developing dementia. Another study found that aerobic exercise led to significantly improved cognitive scores for dementia patients compared to sedentary peers. Strict adherence to diets that target cardiovascular improvement have also shown evidence for reduced incidence of AD. When it comes to language and culture, bilinguals show symptoms of dementia 4 years later than monolinguals — a remarkable result that has been shown not only in Canada but globally as well. Even when comparing the brain health of bilinguals to monolinguals in older age, bilinguals have better cognitive and clinical outcomes at similar levels of neuropathology. When we consider everything together, a pattern becomes clear: lifestyle changes are the best way to prevent and delay the development of dementia.

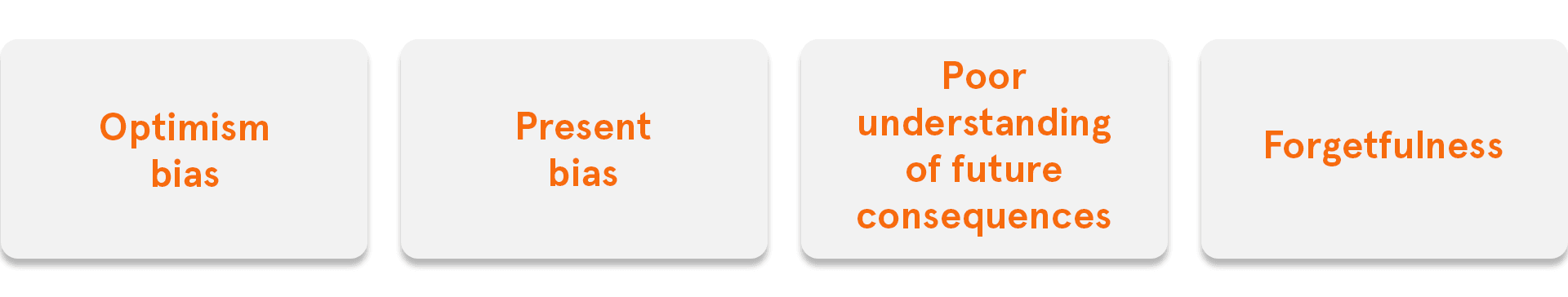

But how do we make these changes, and when? What’s preventing physicians from recommending these lifestyles to their patients? Why aren’t we, as individuals, adopting these beneficial habits and skills on our own? As with any behavior, change is hard! Further complicating the issue is that these lifestyle changes must occur well before a diagnosis of dementia — we’re talking years, maybe decades, in advance. There are a multitude of reasons why patients might not adhere to a new recommended lifestyle, and they include (but are not limited to) the following:

These are just a few of the barriers that get in the way of developing healthy lifestyles that can prevent dementia further down the line. Once a physician recognizes that a patient may need to adjust their current lifestyles for future benefit, some of the following are ways to help patients adopt a new routine:

Ultimately, the goal of any recommended lifestyle change is for the health and wellbeing of the patient: delaying or preventing the effects of dementia in older age and improving the quality of life and enjoyment for the patient in the interim. Considering that a delay of 5 years of AD onset leads to an ~50% decrease in the prevalence of the disease, delaying the development of symptoms through lifestyle interventions is one of the best individual, and therefore societal, changes we can make.