Computer and mobile device apps focused on personal finance have proven popular and represent a $7.5B market globally. Often referred to as Fintech, there are computer and mobile device applications for on-line banking, fraud prevention, saving, borrowing, managing credit, investing, buying insurance, and financial planning.

The benefits include, convenience, accessibility, ability to compare options, better recordkeeping, increased financial literacy, and the ability to create and follow a financial plan. These capabilities are important.

Two thirds of the people in America are merely coping or are financially vulnerable with challenges of spending less than their income, paying bills on time, saving for short term emergencies, saving for the long-term, managing their debt, and maintaining a good credit score. There are Fintech apps that can help with all of these challenges.

The Fintech market is large and growing but many groups may be excluded. Lower income households may have less access to devices and apps. As well, many low to moderate income households are over 50 and have lower usage of Fintech. A BE perspective suggests that there are other challenges in addition to access. With apps for every aspect of personal finances, there is a risk of compartmentalization. All aspects of personal finance are interconnected. With each app focusing only on one aspect (saving or borrowing or investing or credit score, etc.) it is easy to fall into a trap of compartmentalized thinking and focusing on once aspect to the detriment of others.

BEworks’ research on financial planning has identified this compartmentalization as a major contributor to the implementation gap whereby clients do not fall through on the recommendations contained in their financial plan.

This implementation gap is rooted in the way that clients think about their finances, in a compartmentalized way, when they start the financial planning journey. Clients often seek support for one area of their financial lives (e.g., opening up an education savings plan or seeking help with debt management) without connecting these behaviors to other financial behaviors. Ultimately this results in clients receiving a financial plan that is comprehensive and asks them to act on a number of fronts; not something that they expected they would need to do to address the main priority they had in mind.

In the area of credit management, consumers’ attention may not be what it ought to be, simply because they are focused on other aspects of their finances such as saving. Yet, saving more while costly debt remains unpaid is not real progress.

Licensing effect is another concern. In simple terms, licensing effect describes increased self-image and confidence occurring after doing something positive that makes it more likely to feel less guilt or remorse from subsequently doing something that would be viewed as negative. For example, people are more likely to eat an indulgent meal after exercising, thus negating the benefits of exercise.

In the context of personal finances, simply downloading the app may license subsequent self-defeating financial decisions such as borrowing to splurge on an unnecessary purchase.

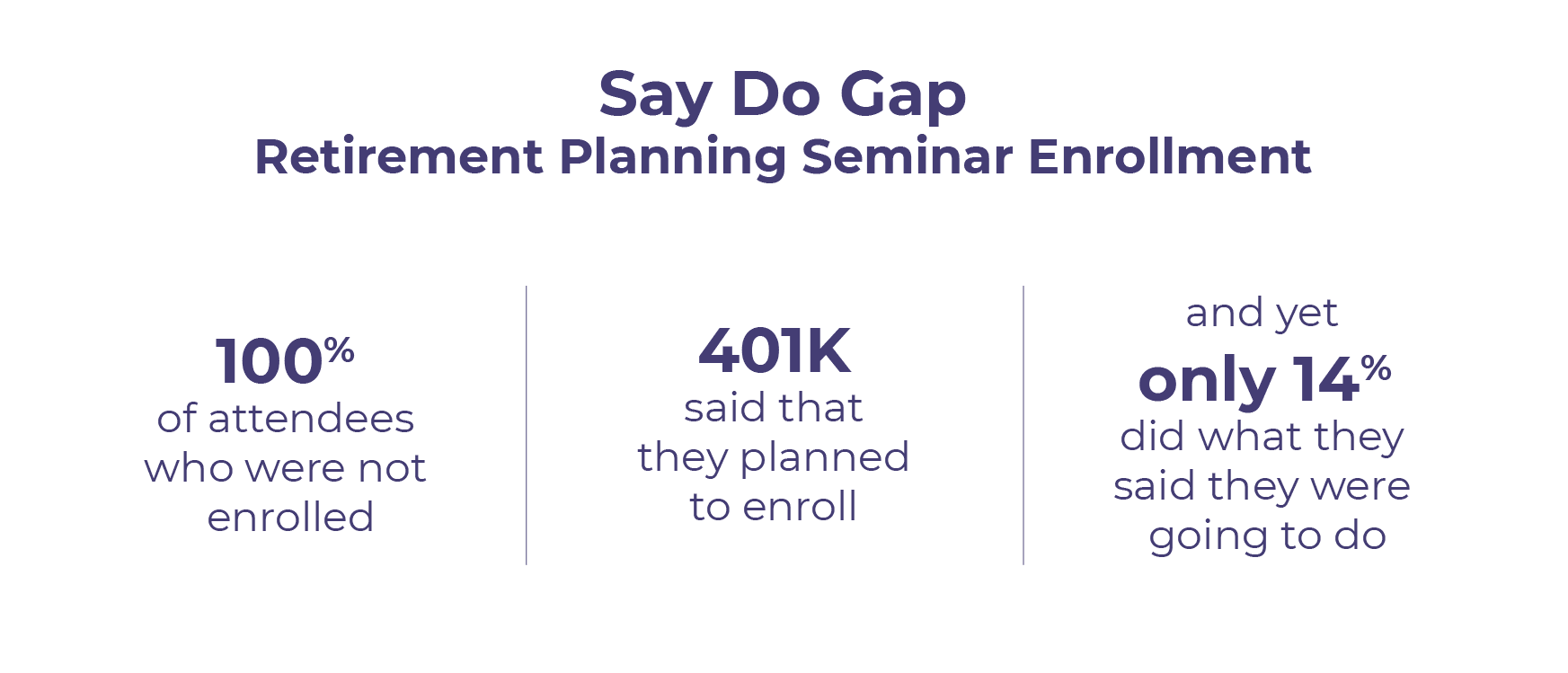

What BEworks refers to as the ‘say-do gap’ is also certainly operative. In a study on attendees of a retirement planning seminar, 100% of attendees who were not enrolled in their company 401K said that they planned to enroll and yet only 14% did what they said they were going to do. Perhaps it was licensing effect, since they felt good about going to the seminar but maybe procrastination, motivation to seek additional information, ambivalence, uncertainty, or other factors prevented action, but the important change in behavior did not occur. Fintech apps may change people’s intentions but changing behavior is much more difficult.

The educational aspect of fintech apps is overstated as well. Apps can help people learn what they should do and should not do but similar to financial literacy, training may increase knowledge at least temporarily, but it fails to achieve the important behavior change.

A small amount of knowledge may also create overconfidence since there is often a gap between what we think we know and what we actually know. In complex, risky consequential, financial decisions, many know only enough to be dangerous.

Saving apps may help in a small way. There are apps that will round-up debit card and credit card purchases and transfer the round-up amount to savings. The default amount however will likely be tiny and will have limited long-term impact.

As well, we know from BE research that people tend to stick with the default and become passive. As a result, they may no longer actively consider whether they are saving enough over time and fail to change their behavior as their income or expenses change.

To overcome compartmentalization, apps should use whole-unit framing to humbly remind users that while their focus is often only on a specific part of financial well-being, there is a larger whole to be aware of and to care for.

Stressing the importance of all aspects (i.e., spending less than income, paying bills on time, having a short-term emergency fund, saving for long-term goals, managing debt, and maintaining a good credit score) are all part of the journey to financial well-being.

Care must be taken to maintain the perception of progress on each stage of the journey to help users build and maintain feelings of agency and self-efficacy. Opportunities for cross-collaboration between apps can enhance the value proposition of each and also ensure better outcomes.

Licensing is not a conscious decision. We do not explicitly tell ourselves that one good deed allows a bad, but we behave as if it does. Addressing the temptation directly can be sufficient to make the reasoning explicit and allow us to see the flaw in our thinking. It also helps to re-frame what we view as good financial behaviors instead as necessary financial behaviors. The result may be that our efforts are not later sabotaged.

Personal finance apps are a land of promise, though they also run the risk of overloading consumers with more choices and decision difficulty than is needed or prudent. The result is often a say-do gap with inaction and decision avoidance due to deferring a decision, being biased towards the status quo, being biased towards doing nothing, or simply overcoming inertia to get started.

The conventional view is that offering consumers a wealth of options for customizing an app is what will “hook” them and drive long-term use. Yet, evidence suggests that technology adoption may actually be promoted best by prioritizing a smaller set of features and making the experience as user-friendly and reinforcing as possible. By reinforcing, we mean connected to personal goals and capable of helping consumers to see that they are making progress.

Overconfidence often results from people’s subjective knowledge (what they think they know) exceeding their objective knowledge (what they actually know). In one BEworks live experiment with a room full of retirement benefits consultants, simply having them answer ten fairly simple questions to test their actual knowledge resulted in them making a more realistic assessment of their expertise and reducing their overconfidence.

Apps can gamify learning and the process allows users to realistically assess what they know privately and in a non-threatening environment. They may then be more likely to seek and follow advice.

There may also be too much reliance on defaults that allow users to become passive rather than active participants. Defaults may reduce choice complexity but to balance the desire to give choice without overloading consumers, a strategy called enhanced active choice may be called upon to help consumers actively shape their in-app experience so that it will support their long-term goals.

For example, imagine an app that consumers download in order to help them build healthy credit behaviors. One default that might be important to put into place would be SMS notifications that the consumer will automatically receive after they make a purchase with their credit card. This notification would serve to trigger the pain of paying, in other words, making it salient to customers how much money they just spent.

This combats the often intangible nature of spending with credit cards that leads to overspending. This type of default message could help to decrease overspending, though it is an aversive type of notification that consumers might not “opt into” receiving.

Enhanced active choice can be leveraged by telling consumers that this type of notification is a default feature of the app and inviting them to customize some element of the notification, for instance the type of behavior change they would like this notification to help them with – does the consumer want to use these notifications to drive down their spending on coffee, or to reduce large sum expenditures on their card?

By giving consumers some choice within a mostly fixed choice architecture, the motivation becomes internalized rather than being an external control. It is possible to preserve feelings of autonomy, self-determination, and motivation, while also introducing aspects of the journey that consumers might not have selected for themselves.

This article is part of our Credit in the New Normal Series which dissects 5 credit trends brought on by the pandemic with a behavioral lens. To read the other articles in the series, click here.

If you want to learn more about how the pandemic has changed the way people use credit, watch our webinar recording ‘Credit in the New Normal’