Residential real estate prices have been moving upwards, particularly in the past 5 years, but COVID-19 has accelerated the trend. Termed the great reshuffling, there also seems to be a trend to move out of dense urban areas to areas with a lower population density. The pandemic has made many people less comfortable in crowded spaces. As well, with most people spending much more time at home, and with many needing to trade up and find more space for a home office, the trend is understandable. With outflows from cities, rents are dropping in many urban cores.

One driver of home price appreciation is the low-interest rates maintained by central banks to support economies during COVID-19, but these low rates are also causing what the IMF refers to as excessive risk-taking and stretched valuations. The Bank of Canada notes that household mortgage debt is rising, mortgage credit quality is declining due to over-extended buyers with high loan to value and high loan to income ratios, and now over 20% of housing demand is driven by investor speculation.

The structure of the real estate industry often reinforces the speculative bubble with blind bids, no price discovery, and commission-driven agents manipulating the sales process to create bidding wars. That type of behaviour is now illegal in the investment industry.

The Bank of Canada has developed a behavior model, the House Price Exuberance Indicator, identifying extrapolative price expectations where expectations of price increases lead to speculative buying and the price appreciation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy driving yet more speculation. In the short term, the housing supply cannot respond quickly to the demand.

Similar patterns are seen globally. In the US, purchases of second homes reached 14% of all home purchases and have doubled in a year. The concern globally is that the extrapolative price expectations are setting up a bubble that will eventually burst. Despite massive deficits driven by an accommodative monetary policy, including stimulus payments to consumers, inflation has been unexpectedly tame. But a rise in inflation expectations would trigger a re-pricing downwards.

The rational economic perspective identifies excessive risk but can’t explain the behaviour. A BE lens identifies numerous drivers of the behaviour.

For example, the Dunning-Kruger effect describes how people overestimate their knowledge and capabilities and tend to overestimate even more when they have less knowledge.

People may overestimate their understanding of the complex calculations regarding real estate. Mortgage costs and rental expenses must be subtracted from rental income and this amount is often negative.

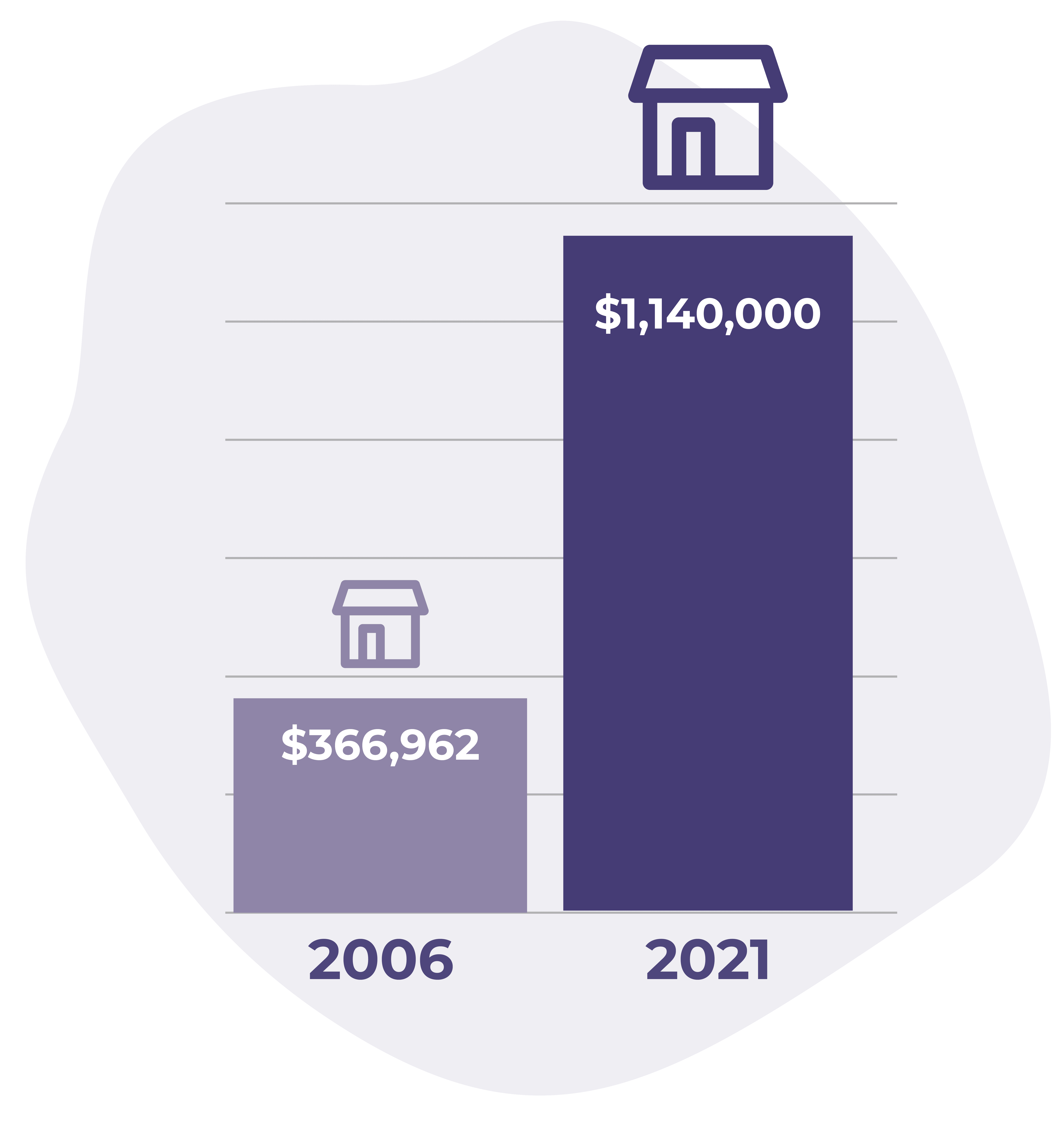

Even with all-cash transactions, people are poor at calculating their expected return on investment properties. The average home in Toronto in 2006 cost $366,962 and accumulated in value to $1,140,000 in 2021.

The returns seem impressive. Many would say their gain is 311% ($1,140,000/$366,962) and they might compare this to gains in the stock market. But the net gain on the original price is actually 211%. Adding back the original purchase of 100% leads to the gross price of 311%. The appropriate figure to compare to alternative investments is the net gain of 211%, not the gross of 311%.

As well, people find it difficult to calculate the compound annual return. The naïve estimate of the annual return over 15 years would be 14% annually (211%/15). This however ignores the impact of annual compounding. The actual annual compound rate of return is 7.8%.

People also ignore real estate transaction costs, sales taxes, property taxes, and maintenance which alone is 1% per year. Subtracting just annual maintenance leaves a net annualized return of 6.8%. This is still impressive but 6.8% is far less than the rough estimate of 14% that people rely on for this complex, risky, consequential decision.

In comparison to an alternative investment, the S&P 500 index, which returned 10.6% annualized over the same period, housing as an investment yielded 3.8% less per year.

In absolute, this doesn’t seem like much, but it again ignores the effects of compounding. For an average 35-year-old home buyer purchasing an investment property with cash, the incremental return from the index would mean a level of wealth over three times higher at age 65. People need homes but they also need to stop looking at housing speculation as the no-risk, no-fail, best-ever investment strategy.

Even an economic comparison of renting versus owning is a complex problem. Once again, people fail to consider real estate transaction costs, property taxes, insurance, maintenance, mortgage interest, and the opportunity costs of foregone income on alternative investments as costs of homeownership when considering renting versus buying.

Rent is often considered wasted money since it goes to someone else, but we forget that mortgage interest goes to the bank so economically, there is no difference.

People also argue that buying is better than renting because they are paying down their principal and building equity. Renters however can also build equity monthly by taking the difference in what they would pay on a mortgage and the lower amount they pay on rent and investing in alternatives like a stock market index fund but with higher returns as demonstrated above.

In the long run, owning a home and renting the same home should have similar economic cost. As rents decline, it becomes economically more attractive to sell the home, invest the capital in an alternative investment with higher returns, and rent similar accommodations instead.

This will eventually drive rents up and home prices down to restore equilibrium. In Canada, the last decline in real home prices lasted over a decade between 1989 and 2000.

Ownership has been more expensive than renting since Q2 2006 and homes are now 78% above their rental value. After 21 years, the risk of a correction is only growing.

Social proof describes our tendency to attend to and mimic the attitudes, opinions, and behaviours of others. We can even do so when the evidence we see clearly demonstrates that those opinions are incorrect.

In a famous set of experiments dating back to 1955 and replicated countless times, the Asch Conformity Experiments showed that an individual would follow the majority opinion of a group of people judging something as objectively verifiable as which of three lines on a piece of paper is longer.

Even when presented with contradictory evidence in black and white, people would accept the opinion of the majority. People may be able to calculate the correct effective return on housing speculation but, with the majority holding a different but incorrect opinion, they dismiss their own conclusions as somehow incorrect.

A related BE perspective suggests that the appreciation in house prices is a speculative bubble.

Referred to as the herding effect in financial markets, this is also called the bandwagon effect. When careful analysis is replaced by decision-making based purely on following the actions of others, the metaphor of a herd of animals, perhaps lemmings, rather than intelligent humans seems appropriate.

Technical analysis, which identifies trends in markets and exploits the trend may become a self-fulfilling prophecy (at least in the short term) when the trend is extrapolated ever upwards. It is a curious coincidence that the speculative bubble in tulip bulbs in 1637, in what is now the Netherlands, also occurred during a pandemic.

The recent GameStop bubble, where the share price was driven far above its intrinsic value, is an example of apparently boundedly rational financial decision-making with very real costs.

BE also identifies fear of missing out (FOMO) as a factor in home speculation. We have an apprehension to losing out on rewards that others are experiencing.

With social media more pervasive, we are increasingly aware of the behaviour of others. Stories of apparently easy riskless profit from buying and flipping real estate creates FOMO.

Realtors have some great social media sites with beautiful homes and claims of easy profits. Prospect theory describes our aversion to losses and demonstrates that, paradoxically, we will in fact take risks to avoid losses. Rather than lose out on these apparent riskless profits, people are motivated to risk their wealth in real estate.

But the real risk may be underappreciated. Representativeness heuristic, describes our tendency to extrapolate current conditions forward without anticipating future events that may alter the trend. We ignore the base rate, in this case the historical incidence of real estate corrections.

The focusing illusion has us attending solely to the trend in home prices; we become mesmerized by the trend. We ignore the underlying psychological drivers and all of the other macroeconomic factors that affect home prices. The rhetorical question, “What could go wrong?” comes to mind.

Countering the BE perspective, the greater fool theory suggests that the speculator may be rational. They may be fully aware that they are apparently being a fool by purchasing an asset at a price far above its intrinsic value, but they expect a greater fool to buy it from them for an even more inflated price.

In an empirical study, the greater fool theory explained the stock market bubbles and subsequent crashes in the stock market in China in 2007 and 2015.

The lesser fool ignores the risk of not finding the greater fool in time. Like a pyramid scheme or a game of musical chairs, somebody loses when the music stops and we only know that it will stop, not when.

Much of the appreciation in real estate can be traced to heuristics and biases rather than sound investment fundamentals. Countering these is important to protect lenders, investors, and renters alike. But the task is not always simple. Helping people realize they know less than they think they do is difficult to accomplish without generating resentment and a wounded ego.

One way to reduce the Dunning-Kruger effect is to encourage people to test their knowledge in private. Numerous helpful calculators are available online (e.g., rent or buy, home mortgage affordability, return on real estate investment, etc.).

Independently completing these types of calculations and then comparing the results to online calculators will illustrate the complexity and allow a personal reassessment of expertise; but in private. A more realistic assessment of knowledge and a feeling of accomplishment and learning may then replace the illusion of expertise.

Helping people overcome the effects of herding, social proof, and conformity requires that we encourage them to actively seek contrarian opinions.

Confirmation Bias leads us to selectively attend to and believe information that confirms existing beliefs. Instead of reading real estate newsletters and browsing sites on real estate, often promoted by realtors listing properties and hoping to earn commissions, we should actively seek contrarian sites that discuss the risks of real estate to ensure that our opinions are balanced.

We know that not everybody is investing their wealth in real estate. Communications strategies can overcome this perception through dynamic social norms.

Communicate a balanced view, such as, “An increasing number of people are cautiously considering the high valuations in real estate right now…” along with the injunctive norm “…and you should too”.

People experiencing FOMO are often in a charged emotional state and more likely to be basing opinions on emotions rather than facts and analysis.

The bidding wars and limited time periods for offers are tactic realtors use to encourage emotional rather than unboundedly rational decisions. That alone should make us wary.

Setting up limits and pre-committing to abiding by the limits is important. For example, if a real estate investment offers an attractive return, but only if it can be purchased for less than $500,000, pre-commit to $500,000 as the maximum price. Otherwise, there will be regret when the emotions cool and the lower return on the higher price is calculated.

For housing rather than investing, comparing the rental cost of similar properties and explicitly acknowledging that paying more every month to own a property than it would rent out for is an uneconomical prospect.

If “ownership” has a utility value for a buyer, (e.g., It’s worth up to $1,000 a month to own this property rather than rent it or a similar one), that amount should be explicitly factored into the decision. Committing in advance, before the emotions take charge of reason, can blunt the effects of FOMO.

Representativeness heuristic loses its power when we acknowledge it and become aware that it can be affecting us. As with all heuristics, wariness and careful second thought allows us to modify our judgement. In general, heuristics can simplify decision-making and allow us to make the hundreds of decisions we make every day.

It is important however, to recognize that heuristics have no place in complex, risky, consequential decisions. Choosing the wrong coffee will create transitory dissatisfaction. A real estate transaction can have life-changing consequences.

With focalism, focusing narrowly on the trend in real estate for example, can be countered by spending some effort to think of contrary outcomes. Literally asking, “What can go wrong?” leads us shift from an intuitive mode of thinking to an analytical mode and to consider other factors affecting the attractiveness of real estate.

The risk of following the greater fool theory is that it leads to buying an asset at a price above its fundamental value. As long as the greater fool does come along, the lesser fool can profit. This neglects the critical factors of timing and market intelligence.

When real estate markets cool, it can be sudden and unexpected. Inventory grows and days on the market lengthen while prices soften and begin to slide. Once it is noticed, it is too late.

A slide becomes a crash as speculators race for the exits. We also often forget that when there is a mortgage on a property, there is leverage. Leverage multiplies gains but also multiplies losses. The slide in value can erase all of the equity in the home and more leading to a loss of over 100% of the investment.

Spending some time contemplating exit strategies is sobering. Spending some time considering how we can anticipate the market top before everyone else does and thinking about how long it would then take to sell the property, and whether you can walk away with some equity left is also sobering.